Beyond the Liberal Mirage: Why American Politics Is a Closed Loop

Beyond the Liberal Mirage: Why American Politics Is a Closed Loop

Beyond the Liberal Mirage: Why American Politics Is a Closed Loop

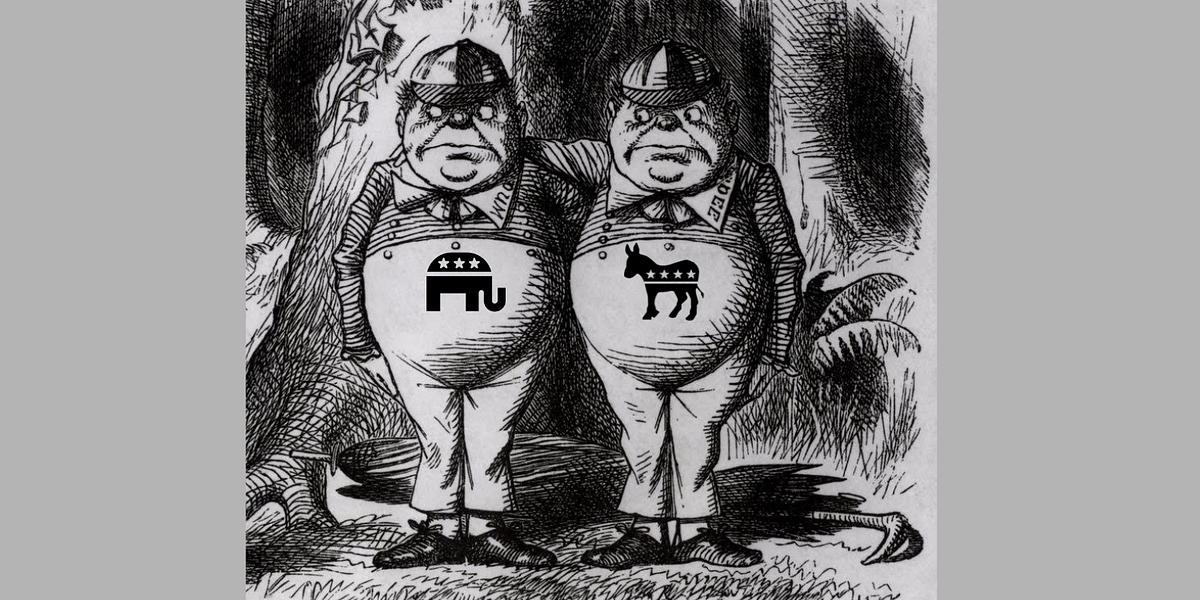

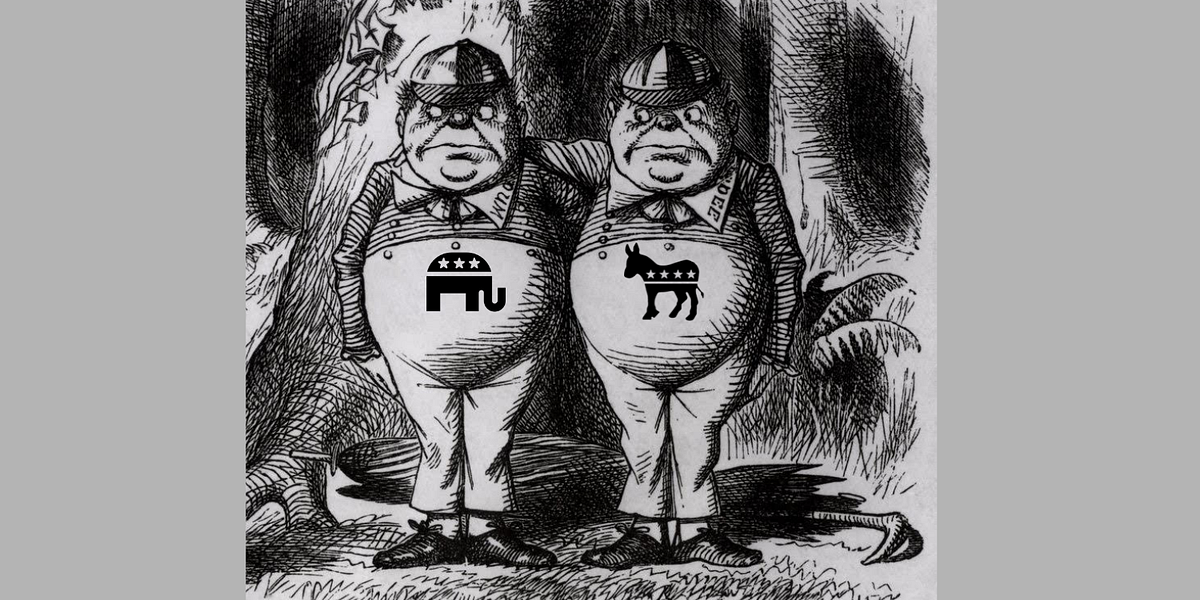

The Illusion of Choice

What Americans call political diversity is actually ideological uniformity. Turn on any news channel, scroll through any political debate, and you’ll see the same tired performance: conservatives versus liberals, Republicans versus Democrats, each side convinced they represent fundamentally different worldviews. But here’s what I’ve come to understand as a socialist looking at this spectacle from the outside — they’re all playing variations of the same tune.

Conservatives, liberals, and even libertarians aren’t offering different philosophical frameworks. They’re offering different flavors of the same ice cream: liberalism. The marketing makes them seem distinct, even opposed, but strip away the branding and you find they all believe in the same core values — just different approaches to achieving them.

This confusion runs so deep that when progressives push for reforms like universal healthcare or wealth taxes, they get labeled as “radical leftists” when they’re actually just trying to make the existing liberal-capitalist system function closer to its stated ideals. True leftist positions — like worker ownership of the means of production or democratic economic planning — don’t even register in mainstream political discourse because they fall outside the artificially constrained liberal framework that defines America’s political vocabulary.

Unmasking the Liberal Consensus

At their very core, conservatives, liberals, and libertarians all operate within the classical liberal tradition that emerged from the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century. They all accept:

- Individual rights as the foundation of society

- Private property as sacred and natural

- Market relations as the default way of organizing economic life

- Constitutional government with checks and balances

- The basic legitimacy of democratic institutions (though they may disagree on their scope)

The differences people get so heated about are really just different emphases within this shared framework. Conservatives might say they want minimal government interference in the economy while liberals want more regulation, but both accept that the economy should be organized around private ownership and market exchange. Libertarians take classical liberalism to its logical extreme, but they’re still working within the same philosophical boundaries.

When I say this is about marketing, I don’t mean the policy differences are trivial — they have real impacts on people’s lives. What I mean is that the ideological packaging makes these tactical disagreements appear to be fundamental philosophical divisions when they’re really just different management styles for the same basic system.

Libertarianism perfectly illustrates this point. Libertarians present themselves as radically different from both conservatives and liberals, advocating for minimal government and maximum individual freedom. But libertarianism is actually what you get when you push liberal principles of individual rights and limited government as far as they can go while still maintaining private property and market relations. The libertarian’s “radical” position of eliminating most government functions isn’t a departure from liberalism; it’s liberalism without the moderating influences that other liberals accept as necessary to manage capitalism’s contradictions. This is why libertarianism sits even further right than conservatism — conservatives at least accept some government intervention as necessary, while libertarians want to strip it down to almost nothing.

Here’s where American political discourse gets it fundamentally wrong: liberalism isn’t the “left” — it’s the center of the political spectrum. In mainstream American conversation, “liberal” gets treated as synonymous with “left-wing,” but this is a profound misunderstanding that distorts our entire political vocabulary.

The real political spectrum runs like this: To the left of the liberal center, you have progressivism (what Americans often mistakenly call “liberalism”), then socialism, then communism, then anarchism. To the right of the liberal center, you have conservatism, then libertarianism, then far-right extremism.

But American discourse compresses this entire range into a false binary where “liberal” means left and “conservative” means right, completely erasing actual left-wing positions from the conversation. When Americans say someone is “liberal,” they’re usually describing what should properly be called progressive — someone who wants to reform the liberal system to make it work better, not someone who wants to replace it entirely.

This linguistic confusion isn’t accidental. It serves to make the liberal framework appear to encompass the full range of legitimate political thought, when in reality it represents just the center position with some variations to either side.

The Structural Contradiction

Here’s where it gets interesting from a theoretical standpoint. Capitalism developed as a purely economic system focused on market relations and private ownership. But any economic system needs a political and social framework to sustain it, and liberalism provided that framework for capitalism.

The problem is that these two systems have contradictory logics. Liberalism promises political equality — the idea that all individuals have equal rights and equal say in democratic governance. But capitalism requires economic inequality to function. Someone has to own the means of production, someone else has to sell their labor. Capital needs to accumulate, which means wealth concentrates. The system literally cannot work without creating and maintaining class divisions.

This isn’t some unintended side effect –- it’s structural. Political theorist and historian Roy Casagrande describes how liberalism essentially became capitalism’s philosophical framework, providing the ideological justification for a system that contradicts liberalism’s own stated values.

Even early Enlightenment thinkers who developed liberal theory recognized this tension. They understood that capitalism’s tendency toward inequality could undermine political equality, but they believed this could be managed through institutions and reforms rather than by questioning the economic system itself.

The Evidence: When Theory Meets Reality

This contradiction isn’t just theoretical — it plays out in concrete ways that affect real people’s lives.

Black Americans provide the clearest example of how formal political equality coexists with systematic economic exclusion. Despite decades of civil rights legislation, anti-discrimination laws, and diversity initiatives –- all liberal solutions — the racial wealth gap has barely budged. Median Black family wealth remains about one-tenth that of white families. This isn’t because liberal reforms haven’t been implemented, but because they address symptoms while leaving untouched the underlying system that created and maintains these disparities.

The caste system that affects Black Americans operates alongside the class system. When economic downturns happen, Black Americans face distinct and often disproportionate impacts not just because of class position but because of how race and class interact under racial capitalism. Liberal frameworks struggle to address this because they’re designed to treat race and class as separate issues rather than understanding how they’re systematically intertwined.

Native Americans face even starker contradictions. They’re simultaneously sovereign nations and colonial subjects, with formal treaty rights that exist alongside ongoing land theft and resource extraction. The reservation system creates a form of internal colonialism that liberal political theory can’t even properly name, let alone address. How do you reconcile individual property rights –- a cornerstone of liberalism — with collective indigenous sovereignty and traditional land use practices? You can’t, which is why liberal solutions consistently fail to address the root issues.

Latino Americans demonstrate how immigration status creates tiered citizenship that serves capital’s need for exploitable labor. Some have formal rights while others are deliberately kept in precarious legal positions that make them more vulnerable to exploitation. This isn’t a policy oversight — it’s exactly what the economic system requires to maintain cheap labor pools.

Even European social democratic models, often held up as examples of successful liberal reform, reveal these same fundamental contradictions. Sweden’s domestic equality coexists with arms exports to authoritarian regimes. Germany’s strong worker protections rely on exploiting Southern European labor through EU economic structures. The welfare state ameliorates capitalism’s worst effects domestically while often intensifying exploitation elsewhere.

The Progressive Trap

Here’s what’s particularly revealing: every time progressives push for reforms to address inequality, they’re essentially admitting that capitalism doesn’t naturally produce the outcomes liberalism promises.

Universal healthcare? That’s because market-based healthcare creates inequality. Strong labor protections? Because unregulated capitalism exploits workers. Wealth taxes? Because capitalism concentrates wealth. Affirmative action? Because “merit-based” systems reproduce existing inequalities.

Each progressive reform is an acknowledgment that the economic system undermines the political ideals. The more adjustments liberals have to make to capitalism to achieve their stated goals of equality and freedom, the more they’re proving that socialism’s analysis was correct — that you can’t have genuine political equality while maintaining private ownership of the means of production.

This is why liberal reforms, no matter how well-intentioned, keep failing to address root causes. They’re trying to solve systemic problems with tools provided by the same system that created those problems. It’s like trying to fix a broken foundation by rearranging the furniture.

Beyond the Liberal Horizon

Understanding this helps explain why American political discourse feels so constrained and circular. When both major parties operate within the same fundamental framework, when the boundaries of “realistic” policy are drawn by that framework’s limitations, genuine alternatives become literally unthinkable within mainstream political conversation.

Socialism offers something different because it addresses both the economic system and its supporting political structures. Instead of trying to manage capitalism’s contradictions, it proposes replacing the system that creates those contradictions in the first place. Worker ownership of the means of production. Democratic planning of economic priorities. An economic system designed to serve human needs rather than accumulate capital.

This isn’t utopian thinking — it’s practical recognition that the problems liberalism struggles to solve are inherent to the economic system liberalism was designed to support.

Breaking the Frame

The first step toward real political alternatives is recognizing how narrow the current frame actually is. What gets presented as the full spectrum of political possibility is really just different management strategies for the same basic arrangement of economic and political power.

Once you see this, a lot of things start making sense. Why Democrats and Republicans seem to agree on so much when it comes to fundamental economic structures. Why reforms that sound transformative end up changing so little. Why the same problems keep recurring regardless of which party is in power.

We live in a liberal Enlightenment society with capitalism as its economic model. Until we’re willing to question that framework itself, we’ll keep having the same debates, implementing the same types of solutions, and wondering why the same problems persist.

The real political spectrum is much broader than American discourse suggests. It’s time we started acting like it.

This article represents the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of The Detroit Socialist or Metro Detroit DSA as a whole.